Georgian Wine Made in Clay: Eight Thousand Years of History

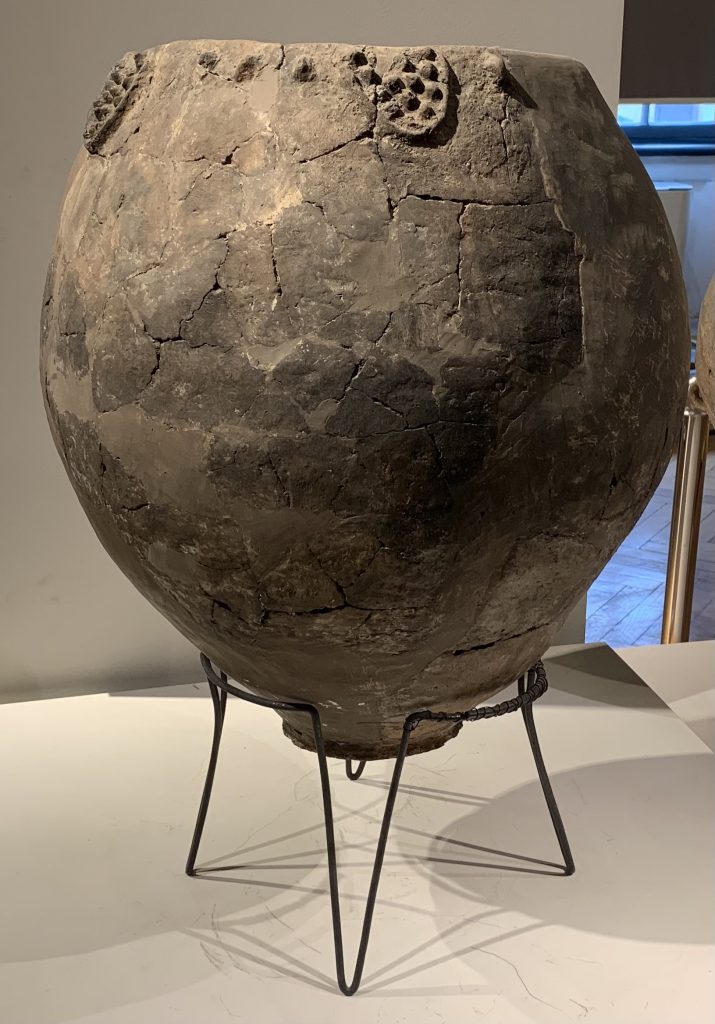

No one knows precisely when our ancestors began making wine, but the best evidence suggests it was in the Georgian Caucuses where an eight-thousand-year-old clay jar (shown here at the Georgian National Museum) adorned with grape bunches and containing residual wine compounds was recently discovered south of Tbilisi. For thousands of years continuing to the current day, wine in Georgia was made in large clay jars called qvevri. We tasted numerous wines made in qvevri on our recent trip to Georgia, and shortly we’ll be writing a full report on Georgian wine.

Traditionally, the winemaking process was straight-forward. Juice from foot-stomped bunches of grapes, both red and white, in a large wooden trough flowed into the qvevri followed by the addition of skins, stems and seeds; fermentation ensued and when finished the qvevri top was sealed with a stone lid; several months later the top was opened and the wine drunk. The result was a wine, either amber or red in color (depending on the grapes used), that was savory, dry and tannic.

Making a Qvevri

The qvevri itself has evolved over time, becoming more conical in shape, larger, and buried in the ground, both for natural temperature control and to provide support for the vessel itself. Today, the making of a qvevri, typically 1000-2500L in size, is a work of art that takes several weeks. We visited qvevri master Zaza Kbilashvili (shown here firing a qvevri) in the small village of Vardisubani to learn how it’s done. A qvevri is built from the bottom up by laying clay “logs”, each layer of which must dry before the next is laid. When finished, the qvevri is dried for a few weeks before being fired several days at a temperature exceeding 1100°C in a bricked-in kiln. After firing, beeswax is typically added to the interior to smooth the surface and inhibit the leaching of minerals.

The qvevri itself has evolved over time, becoming more conical in shape, larger, and buried in the ground, both for natural temperature control and to provide support for the vessel itself. Today, the making of a qvevri, typically 1000-2500L in size, is a work of art that takes several weeks. We visited qvevri master Zaza Kbilashvili (shown here firing a qvevri) in the small village of Vardisubani to learn how it’s done. A qvevri is built from the bottom up by laying clay “logs”, each layer of which must dry before the next is laid. When finished, the qvevri is dried for a few weeks before being fired several days at a temperature exceeding 1100°C in a bricked-in kiln. After firing, beeswax is typically added to the interior to smooth the surface and inhibit the leaching of minerals.

Qvevri Winemaking Today

The making of wine in qvevri has remained basically the same for thousands of years, but commercial winemakers have fine-tuned the process. The grapes are first destemmed and crushed with the juice sent to qvevri and skins and stems added after. While home winemakers, at least in Eastern Georgia, follow the traditional practice of leaving the wine on stems and skins for six months before opening the qvevri, most commercial winemakers take a more nuanced approach. Stems, especially unripe ones, add tannins and bitter, green notes to wines, so many winemakers forego the use of stems altogether, while others dry them before adding to the fermenting wine. In Western Georgia where the stems are often green, they are rarely used.

Skins are essential to the making of qvevri wine, but winemakers vary in terms of the percent of skins used and the time of skin contact. Good winemakers constantly monitor the wine using a wine thief inserted into a hole in the lid and may rack the wine off the skins, stems and seeds as early as 3 months after fermentation depending on the vintage and grape variety. They may also rack off separately the clear, top part of the cuvee and the bottom part that has been in constant contact with the gross lees. The bottom part is then given several rackings to allow solid matter to settle out. Some winemakers even provide a degree of temperature control, either cooling the cellar in which they’re located or in rare cases using piping to cool the qvevri itself.

The most critical and time-consuming part of making wine in qvevri is the cleaning after winemaking, which must be done by hand with repeated washes of lime and citric acid solutions. Cleaning is laborious, and producers continue to experiment with new methods. Misha Dolidze of Casreli Marani uses an ozone generator. Beka Jimsheladze of Vellino burns sulphur in the qvevri prior to filling. The expense of cleaning contributes to the high cost of producing qvevri wine according to Giorgi Dakishvili of Orgo/Teleda.

Qvevri Wines

If qvevris are made and fired appropriately, most winemakers claim the qvevri is inert. What makes qvevri wine different is contact with skins and stems, and this is most notable for wines made with white grapes. These “amber” wines gain their color from the skins, and they are lower in acidity and higher in tannins than white wines not given skin contact. They are less fruity and more savory with descriptors like dried fruit, honeycomb, and dried herbs. Made like red wines, they should be treated like red wines and are best consumed with food. Most benefit from decanting and aging in bottle, and the wines change in character as the meal goes on.

If qvevris are made and fired appropriately, most winemakers claim the qvevri is inert. What makes qvevri wine different is contact with skins and stems, and this is most notable for wines made with white grapes. These “amber” wines gain their color from the skins, and they are lower in acidity and higher in tannins than white wines not given skin contact. They are less fruity and more savory with descriptors like dried fruit, honeycomb, and dried herbs. Made like red wines, they should be treated like red wines and are best consumed with food. Most benefit from decanting and aging in bottle, and the wines change in character as the meal goes on.

As with any other wine, amber wines not made correctly or made in unclean qvevris can be unpleasant. Green stems contribute tannic bitterness. Under ripe or sun burned skins can also contribute off flavors. On the other hand, grapes that are phenolically ripe from meticulously managed vineyards can make beautiful, balanced, fresh wines in qvevri just as they do in stainless steel. One of the most refined wines consumed on our trip was a 2022 Lagvinari Rkatsiteli made by master viticulturist Eko Glonti that spent 7 months on the skins.

Qvevri wines from Georgia are very reasonably priced, but they may be difficult to find at your local wine store. These stores have a good selection that can be ordered online: Astor Wine and Spirits in New York, K&L Wine in San Francisco, and Batch 13 and Potomac Wines in Washington DC.